They bought Harry’s school books in a shop called Flourish and Blotts where the shelves were stacked to the ceiling with books as large as paving stones bound in leather; books the size of postage stamps in covers of silk; books full of peculiar symbols and a few books with nothing in them at all. (Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone)

Books of magic and magical books are staples in fantasy and horror literature. With no physical laws to inhibit them, what flights of fancy may authors not conjure up to enchant us?

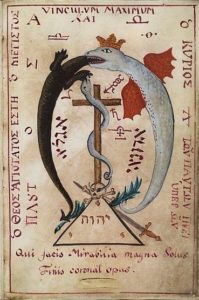

A page of the legendary Cyprianus, or “Black Book.” 18th Century. Latin, Greek, and Hebrew text appears on the page, alongside obscure symbols. Some say the text of the book was meant to be read backwards. Courtesy of Wellcome Images.

The granddaddy of mystical tomes is the Necronomicon, an invention of horror writer H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) which he employed in a number of his short stories and novels. Lovecraft endowed his grimoire (a book of magical spells and talismans) with such a detailed history that many folk have believed it real. Stories abound of library patrons requesting access to the “worm-riddled volume.”

Lovecraft’s descriptions of the physical book are more evocative than detailed:

[He] appeared one day in Arkham in quest of the dreaded volume kept under lock and key at the college library – the hideous Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred in Olaus Wormiu’s Latin version, as printed in Spain in the seventeenth century. (“The Dunwich Horror”)

Another literary grimoire appears in the novel and musical Wicked.* Author Gregory Maguire (b. 1954) details both the binding and content of the Grimmerie which Elphaba consults for useful spells and information:

She went to the Grimmerie and hauled open its massive cover – leather ornamented with golden hasps and pins, and tooled with silver leaf – and pored through the tome to find what makes people thirst for such authority and muscle.

The Grimmerie described poisoning the lips of goblets, charming the steps of a staircase to buckle, agitating a monarch’s favorite lapdog to make a fatal bite in an unwelcome direction.

There were elegant attenuated drawings in blood red and gold leaf, on the front and rear elevations of (it seemed) an angel, with notes in a fine hand on the aerodynamic aspects of holiness. The wings flexed up and down and the angel smiled with a saucy sort of sanctity. “And a recipe on this page. It says ‘of apples with black skin and white flesh: to fill the stomach with greed unto Death.”

MOVABLE TYPE

The best examples of literary spell books play on the tradition of the written word as imbued with magic. Pre-literate populations looked on both writing and reading with deep suspicion and it is no coincidence that the word for casting an enchantment is “spell.”

Elphaba’s Grimmerie is clearly an enchanted book meant only for the serious reader. The witch herself must work to understand it:

“Look how it scrambles itself as you watch.” She pointed to a paragraph of hand-lettered text. Sarima peered. Though her skill at reading was minimal, she gaped at what she saw. The letters floated and rearranged themselves on the page, as if enlivened. The page was changing its mind as they watched it. The letters clotted together in a big black snarl, like a mound of ants.”

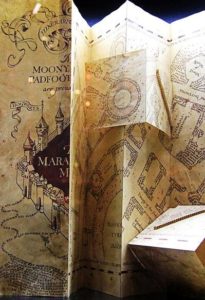

A similar device is used in the Harry Potter books of J.K. Rowling (b. 1965), books filled with enchanted books, parchments, letters, and other printed objects. Those who have read the books or seen the movies well know that in Harry’s magical world pictures come alive. So does a document known as The Marauder’s Map. The map has the appearance of a “square, very worn piece of parchment with nothing written on it” until it is touched by a magician’s wand and given a command, usually “I solemnly swear that I am up to no good.” It then reveals its true purpose:

It was a map showing every detail of the Hogwarts castle and grounds. But the truly remarkable thing were the tiny ink dots moving around it, each labeled with a name in minuscule writing. Astounded, Harry bent over it. A labeled dot in the top left corner showed that Professor Dumbledore was pacing his study; the caretaker’s cat, Mrs. Norris, was prowling the second floor; and Peeves the Poltergeist was currently bouncing around the trophy room. (Harry Potter and The Prisoner of Azkaban)

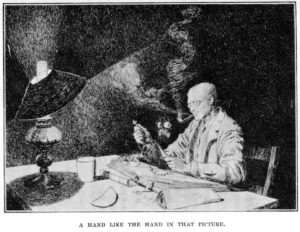

Text that moves or changes, appears or disappears is the very stuff of occult fiction. Horror writer M.R. James (1862-1936) uses mystical text frequently in his short satires – a bit of Latin schoolwork with an ominous message which disappears after reading, a slip of paper with runic symbols and a death wish, a scrapbook of medieval manuscripts that imprisons a fearful demon, a will that translates itself from an unknown language to English when in the right hands.**

The esoteric nature of magical documents requires that they be difficult to interpret. While the Grimmerie employs movable type and The Marauder’s Map is cloaked in invisibility, other magical books are written in ancient – preferably dead – languages: Latin, Greek, Ancient Hebrew and Arabic are favorites; others are written in code.

Perhaps the most unusual literary spell book appears in Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norell by Susanna Clarke, a novel crammed full of books of magic. The chief among these, the Book of the Raven King, is found written indelibly on the body of a beggar. The text, present from birth, is heavily symbolic, seemingly indecipherable, and subject to alteration:

“I have changed! said Vinculus. “Look!” He took off his coat and opened his shirt. “The words are different! On my arms! On my chest! Everywhere! This is not what I said before!” …..

“So what are you now?”

Vinculus shrugged his shoulders. “Perhaps I am a Receipt-Book!*** Perhaps I am a Novel! Perhaps I am a Collection of Sermons!”

“I hope you are what you have always been – a Book of Magic. But what are you saying? Vinculus, do you mean to tell me that you never learnt these letters?”

“I am a Book,” said Vinculus, stopping in mid-caper. “I am the Book. It is the task of the Book to bear the words. Which I do. It is the task of the Reader to know what they say.”

Fortunately, we readers may leave the burden of interpretation to the authors, sit a spell, and enjoy the story.

ॐ

*The novel is subtitled “The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West;” the musical is subtitled “The Untold True Story of the Witches of Oz.”

**From “A School Story,” “Casting of the Runes,” “The Scrapbook of Canon Alberic,” and “The Tractate Middoth,” respectively

***A recipe book

No comments:

Post a Comment