Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, source unknown. The world of John Sanders.

That’s All She Wrote

In 1941 Hannah Dustin French of the Wellesley College Library published an essay entitled “Early American Bookbinding by Hand.” In the essay, she makes mention of American’s first bookbinder:

Bookbinding was one of the very early crafts to be practiced in this country, but where the first book was bound and what it was like we do not know. A bookbinder, John Sanders by name, took the freeman’s oath in Boston in 1636 and purchased a shop for himself there in 1637.

French and other book historians drew their information from an exhibition catalogue published by the Grolier Club, a literary society in New York still in existence. In turn, the editor of that 1907 publication cites a much older work. Unfortunately, A History of American Manufacturers from 1608 to 1860, Volume I, gives no further source for the information.

Thus begins the frustrating search for the elusive Mr. Sanders. It is left to the armchair historian to head down rabbit holes, consult ancient texts and modern search engines, and extrapolate, conjecture, and theorize to come up with a portrait of the man and his work. In the process, she finds many tantalizing topics relating to publishing in early America, from the female owner of the first print shop in the Colonies, to the mass printing of “Indian Bibles” in the 1660s and the Native American called “James Printer” who helped with the translation and typesetting of that publication. She even stumbles upon a 20th century hoax involving a Puritan document and the first bookstore/coffee house in America.

The Freeman’s Oath

To understand a little bit about who John Sanders was, it is a good idea to start with the Freeman’s Oath. That testament was a declaration of loyalty to authority required by both the Plymouth Colony (founded 1620) and the Massachusetts Bay Colony (founded 1630) to be eligible for public office or even to vote in town meetings. As the name makes apparent, the Freeman’s Oath was available only to free men and not to slaves, indentured servants, apprentices, or women. Even then, a man had to demonstrate that he was of “a quiet and peaceful manner” and be sponsored by other freemen.

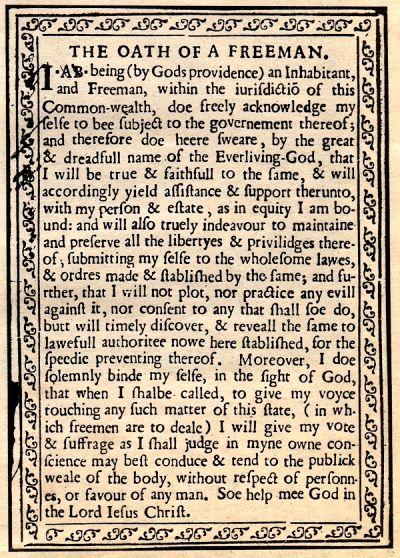

The Oath read, in part,

I [NAME], being, by God’s providence, an inhabitant & freeman within the jurisdiccon of this comonweale, doe freely acknowledge my selfe to be subject to the govermt thereof, & therefore doe here sweare, by the greate & dreadfull name of the eurlyving God, that I will be true & faithfull to the same….

Spellings may vary!

There is no known extant copy of the broadside Freeman’s Oath printed by Stephen Daye in 1639. The document above, touted as a rare find in 1985, turned out to be a hoax perpetrated by infamous forger and murderer Mark Hoffman in a bizarre case in the annals of archival history. Hoffman is currently serving a life sentence at the Utah State Prison.

Signs of the Times

French tells us that Sanders took the Freeman’s Oath in Boston in 1636. This was only six years after the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony of which Boston was the lead town. Although Massachusetts quickly grew to about 20,000 European inhabitants before 1840, it must have been a rough and ready community.

So, the question is begged: what was there to bind? In those days there would have been no book publishers, no newspapers, and no printing press! Indeed, the first printing press in Colonial America arrived by ship from England in 1638, a year after Sanders allegedly set up his bookbinding establishment. Venturing into conjecture now, it is possible his work consisted of repairing and rebinding bibles and hymnbooks for the good people of the colony. Perhaps there was also work binding personal correspondence, hand-written memoirs, and volumes of poetry.

All we don’t know

John Sanders left no signed work behind. Indeed, it would have been highly unusual if he had. Puritans generally frowned on prideful things. We do not know how long he was in the bookbinding trade. Without partnering with a printer, it is doubtful anyone could have made a living by bookbinding alone at that time. The first print shop was set up in Cambridge by the widow Glover and her employee, Stephen Day [or Daye] in 1638. Within three years the press had turned out a broadside of our Freeman’s Oath, an “Almanack,” and the Bay Psalm Book; however, there is no evidence that John Sanders or any other independent bookbinder was associated with this enterprise, which was the precursor to the Harvard University Press.

The history maven turns to online genealogical services in an attempt to find information on Mr. Sanders. Alas, the name Sanders or Saunders is quite common and there is no “match” for a bookbinder in Boston in 1637. It is tempting to identify our bookbinder in one John Saunders of Salem, Massachusetts, with the dates 1613 to 1643. Thanks to previous researchers there is a great deal of genealogical information on this man:

- John Saunders of Salem came to America as a teenager in about 1629, shortly before the official establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which, it should be noted, encompassed both Boston and Salem, 15 miles apart.

- John Saunders of Salem became a “freeman” (i.e. took the Freeman’s Oath) in 1836, the same year as John Sanders the bookbinder. In fact, in a 1906 compilation of freemen in the colony, there is only one John Sanders listed for that year. (List of Freemen, Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1630 to 1691, Exira Printing Company, 1906)

- John Sanders of Salem became a freeman approximately seven years after arriving from England; could it be that he came as an indentured servant and, having completed his service in Salem, hied himself to the big city to try his hand at business?

It is here that the researcher finds herself falling down a rabbit hole lined with the proceedings of various obscure historical societies and hopes for a soft landing, particular after reading the following from a meticulously researched work by a 19th century Saunders:

During the years 1635-38 there were so many of the name of Sanders who came to the new settlement, their advent so united, their means so liberal, and their ability so acknowledged, that one can but infer they were members of one family. (The Founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Sarah Saunders Smith, 1897)

Tools of the Trade

Conjecture is a dangerous business. Better that we use our imagination to picture the establishment of Mr. Sanders. It would likely have been a modest workshop adjoining living quarters. Mr. Sanders no doubt employed the basic tools of the trade: sewing frame, glue pot, beating hammer, and plough. If he did more than simple repairs of existing bindings, he would likely have employed sheep or calf skin over oak or birch boards, using materials readily available in the colony. (A tannery was established in the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the 1630s.) He would likely have manufactured his own tools or employed the services of a carpenter. If he ventured into ornamentation at all, it would have consisted of blind tooling leather covers with simple geometric or natural imagery. There would have been no thought of gilt.

We do not know how long Mr. Sanders remained in business. The historian Hugh Amory, writing in the 1990s, goes one step farther than other writers and states that John Saunders worked until 1651, but, he provides no citation for this assertion. If, in fact, Bookbinder Saunders continued in work through the 1640s he might have found work with the printer of the Bay Psalm Book, then located at Harvard College. If he endured into the 1660s, he might have been involved in the production of the Eliot Indian Bible. In that huge undertaking, he would have had competition from other bookbinders, including one John Ratliffe (or Racliffe).

But all that is a story for another decade.

Not a forgery: The Bay Psalm Book was the first book printed in America. Whether John Sanders might have had a hand in binding the work is unknown.

Sources include:

Leander Bishop, M.D., A History of American Manufacturers from 1608 to 1860, Volume I, 1861, available through Google Books.

Hannah Dustin French, “Early American Bookbinding by Hand,” in Bookbinding in America: Three Essays, 1941.

Lawrence C. Wroth, The Colonial Printer, 1931.

The Grolier Club, The Grolier Catalogue of Ornamental Bookbindings Executed in America before 1850, 1907, available through Google Books.

Hugh Amory, Bibliography and the Book Trades: Studies in the Print Culture of Early New England, essays edited by David D. Hall, 2013.

No comments:

Post a Comment