The life of a printer’s apprentice or “devil” was no picnic. It usually involved long hours of arduous labor for little or no pay with only small hope of advancement. Apprenticeship – until at least the middle of the 19th century – meant a multi-year iron-clad contract of indentured servitude. Runaway apprentices, and there were many, could be hunted down in similar fashion to escaped slaves.

Yet for boys of a bookish bent work in the printing or bookbinding trades offered opportunities to read, write, and mix with the educated. For a few “likely lads” apprenticeship was a springboard toward a literary career.

Silence Dogood was an opinionated widow in old Boston who liked to express herself in lengthy epistles to the New England-Courant. Widow Dogood was also the pseudonym of a 16-year old Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). As an apprentice in his brother James’ print shop, Franklin was frustrated that his literary ambitions were confined to the “occasional ballads” he was allowed to print at the shop and sell on the streets. He hit upon the Silence Dogood persona as a way to express his opinions on a variety of topics in a public forum. His brother’s paper, like many of the day, was hungry for content and happy to print the 14 letters that were slipped under the office door after-hours.

An engraving based on an 1876 oil painting “Young Franklin at the Press” by Enoch Wood Perry, in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

An engraving based on an 1876 oil painting “Young Franklin at the Press” by Enoch Wood Perry, in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

It is easy to see the future patriot and statesman in the widow’s pronouncements:

I am naturally very jealous for the Rights and liberties of my Country, and the least appearance of an incroachment on those invaluable Priviledges, is apt to make my Blood boil exceedingly. I have likewise a natural inclination to observe and reprove the Faults of others, at which I have an excellent Faculty. I speak this by Way of Warning to all such whose Offences shall come under my Cognizance, for I never intend to wrap my Talent in a Napkin. (Silence Dogood letter #2, printed April 16, 1722)

Otherwise, Franklin put his time as apprentice to good use by reading everything he could get his hands on. He would beg, borrow, and buy books, even skipping meals to save up his pennies. (Franklin may or may not have coined the term “A penny saved is a penny earned”.) He also learned the print trade well enough to run the paper while his brother was briefly jailed for offending the local authorities.

A century and a half later Samuel Clemens (1835-1910) found himself in Franklin’s shoes. Like Franklin, he was apprenticed to his brother as a printer’s devil. He was allowed a bit more latitude for self-expression than Franklin, and apparently did not suffer the beatings Franklin endured at the hands of his brother. However, his association with his brother was not without friction of a different kind.

A Young Sam Clemens with a printer’s composing stick spelling out his name in reverse, as it would be for typesetting. The daguerreotype image is sometimes reproduced reversed so that we may read the name “SAM.” The date of the image is estimated at 1850 when Clemens would have been 15.

A Young Sam Clemens with a printer’s composing stick spelling out his name in reverse, as it would be for typesetting. The daguerreotype image is sometimes reproduced reversed so that we may read the name “SAM.” The date of the image is estimated at 1850 when Clemens would have been 15.

Clemens was allowed to contribute humorous pieces to the Hannibal Journal, his brother’s paper. And, like Franklin, he was allowed editorial control during shorts stretches of time when his brother was otherwise engaged. However, his brother Orion did not take kindly to some of Sam’s antics, including his habit of lampooning local figures in the paper. In one case Sam slipped a piece into the paper making fun of what may have been an actual suicide attempt by the editor of a rival paper; the story was accompanied by an unflattering woodcut.

Both Franklin and Clemens ultimately broke the bonds of apprenticeship and “lit out for the territories” – Franklin for Philadelphia where he paid more dues as a printer’s assistant before setting up in business for himself, producing a famous almanac, and entering into the political fray that was to result in the American Revolution. Clemens trained as a riverboat pilot and wandered around the country before returning to the newspaper business and, ultimately, a celebrated career as author and humorist.

“Wanted: An Apprentice to the Printing Business. Apply soon.”[2]

Clemens’ fascination with the printed word took him to the brink of financial ruin. Perhaps remembering the tiresome task of setting type by hand, Clemens – now Mark Twain – invested a huge share of his literary earnings in the development of an automatic typesetting machine, the Paige Compositor. Only two of these monsters were ever made and they didn’t work well. Twain lost his shirt.

In the last year of his life, the famed storyteller gave credit to the years when he paid his dues in the print industry:

One isn’t a printer ten years without setting up acres of good and bad literature, and learning – consciously or unconsciously – to discriminate between the two.” (From essay “The Turning Point of my Life,” Harper’s Bazar [sic], 1910.)

Walt Whitman (1819-92) had fond memories of his days as an apprentice and, like Twain, credited his early experiences with the start of his literary career:

I commenced when I was but a boy of eleven or twelve writing sentimental bits for the old “Long Island Patriot,” in Brooklyn; this was about 1832. Soon after, I had a piece or two in George P. Morris’s then celebrated and fashionable “Mirror,” of New York city. I remember with what half-suppress’d excitement I used to watch for the big, fat, red-faced, slow-moving, very old English carrier who distributed the “Mirror” in Brooklyn; and when I got one, opening and cutting the leaves with trembling fingers. How it made my heart double-beat to see my piece on the pretty white, paper in nice type.” (Whitman, Specimen Days, 1892).

Whitman’s career in printing and publishing gave him a thorough understanding and appreciation of type, design, paper, and binding. He brought these skills to bear on the publication of the various editions of Leave of Grass, his magnum opus, even setting some type himself for the first edition. He obsessed over the exact look of each page, each image, and the binding of each edition. He haunted the offices of the typographers hired to create the book, watching over every detail. In a letter to his brother concerning the 1860 edition, he wrote:

The typographical appearance of the book has been just as I directed it. The printers and foremen thought I was crazy, and there were all sorts of supercilious squints (about the typography I ordered, I mean)—but since it has run through the press, they have simmered down.[3]

The spine of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, second edition, 1856. Whitman included a sentence from a private letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson without that author’s permission: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

The spine of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, second edition, 1856. Whitman included a sentence from a private letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson without that author’s permission: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

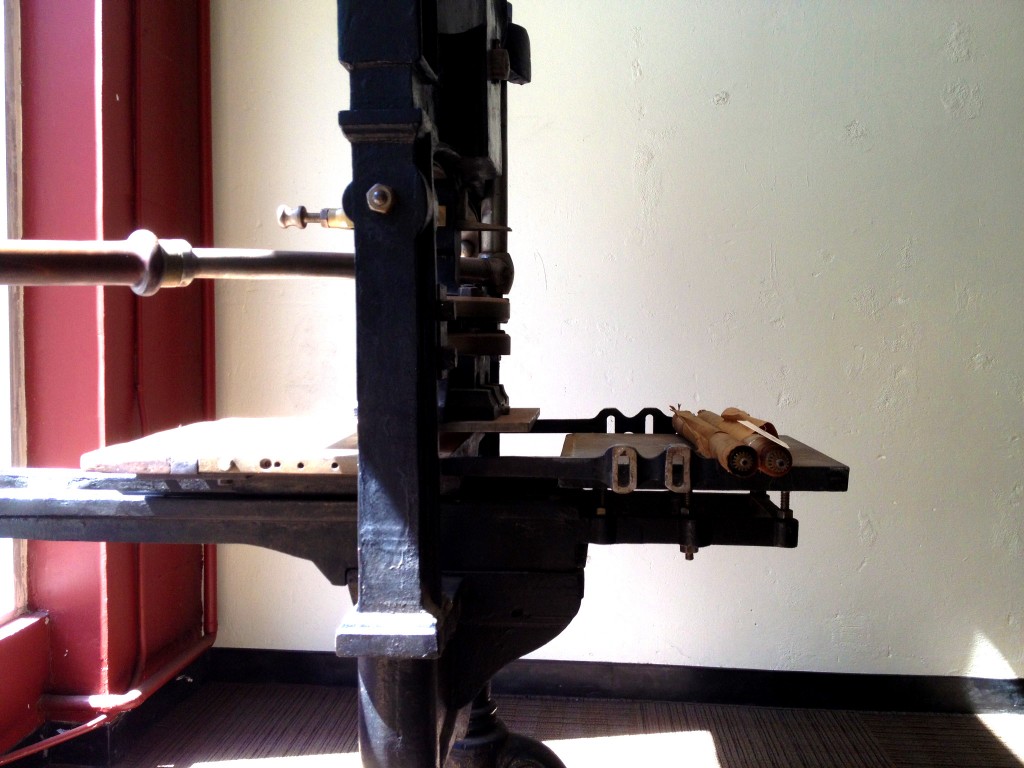

Technological breakthroughs in the printing and publishing industries had a huge influence on Twain and Whitman and their ability to achieve fame and some fortune. In Franklin’s day, the print industry was of an even more manual nature, but still a critical element in the service of political ideas. In 1953 a young Sam Clemens marveled at the progress that had been made in printing upon viewing Ben Franklin’s wooden hand press on display in the Museum of the Patent Office.[4]

The bed is of wood and is not unlike a very shallow box. The platen is only half the size of the bed, thus requiring two pulls of the lever to each full-size sheet. What vast progress has been made in the art of printing! The press is capable of printing about 125 sheets per hours; and after seeing it, I have watched Hoe’s great [iron hand press] machine throwing off its 20,000 sheets in the same space of time, with an interest I never before felt.” (from Mark Twain’s Letters, published 1917)

Franklin the inventor may well have predicted such advancements in the trade of his youth. He was always a printer at heart and felt strongly enough about the profession to incorporate metaphors of printing and bookbinding into the epitaph he wrote for himself as a youth and continued to espouse into old age:

The Body of

B. Franklin, Printer;

Like the Cover of an old Book,

Its Contents torn out,

And stript of its Lettering and Gilding,

Lies here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be wholly lost:

For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more,

In a new & more perfect Edition,

Corrected and amended

By the Author.

When Franklin died, the printers and apprentices of Philadelphia took a prominent spot in his funeral procession.

— Eleanor Boba

Sources:

Branch, Edgar Marquess. The Literary Apprenticeship of Mark Twain. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

The Electric Ben Franklin. Independence Hall Association. http://www.ushistory.org/Franklin.

Fanning, Philip Ashley. Mark Twain and Orion Clemens: Brothers, Partners, Strangers. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2003.

Michelson, Bruce. Printer’s Devil: Mark Twain and the American Publishing Revolution. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006.

The Walt Whitman Archive, Ed Folsom & Kenneth M. Price, editors. The Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. http://www.whitmanarchive.org.

[1] Actual text of advertisement published upon Benjamin’s Franklin running away from apprenticeship at his brother’s print shop.

[2] Actual text of advertisement published upon Samuel Clemens’ running away from apprenticeship at his brother’s print shop.

[3] “Whitman Making Books/Books Making Whitman: A Catalog and Commentary,” by Ed Folsom. The Walt Whitman Archive, http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/anc.00150.html. Visited August 30 and 31, 2014. This extensive article describes Whitman as a book artist, the influence of times on his design work, and the influence of design on the interpretation of his poetry.

[4] The press Clemens saw is now in the collection of the National Museum of American History, part of the Smithsonian Institution. It is associated with Franklin’s sojourn in England in the 1720s and was obtained by an American banker in that country in 1841. Seventy years later it was sold to the Smithsonian.

An engraving based on an 1876 oil painting “Young Franklin at the Press” by Enoch Wood Perry, in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

An engraving based on an 1876 oil painting “Young Franklin at the Press” by Enoch Wood Perry, in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery.